Last night I went to see Vasco Duarte, from Oikosofy deliver a talk on project management, with provocative title NoEstimates – an unconventional approach for the “deliver on time” problem. After getting home, I put together this thread of the most interesting idea in the talk for me. There was enough interest to justify me reading the book, and writing them up in more detail, so I’m sharing my thoughts here for the curious – about the book, and also the talk.

It’s worth declaring where I’m coming to provide some context to this review: professionally, I do a weird grab bag of front and back end development, some devops-y bits, UX and user research, and workshops, through my company, Product Science.

My skills and experience are smeared across all these disciplines, and although I probably identify with product management as a discipline more than anything else, I still enjoy coding, and earn some of my money from doing so.

I don’t think of myself as an agile coach, but as I get older, process becomes more interesting, and I’m thinking about it more and more.

Picking fights with the #NoEstimates hashtag

It goes without saying that using any kind of #no$INSERT_TERM_HERE hashtag to share an idea is:

- quick, somewhat troll-ish way to draw attention to a thing you’re doing

- also a quick way to rile anyone who identifies with that term

Sure enough, getting riled was one of the responses on the evening in the room, as and online, when sharing this thread after event, it felt like I wondered into a agile coach bunfight.

So, I went to @duarte_vasco’s talk about #NoEstimates at @BCGDV’s Berlin offices tonight. I didn’t agree with all of it, but there was one interesting idea was new to me, that I think is worth sharing with folks who couldn’t be there. Warning – trying out a thread: 1/8

— Chris Adams – @mrchrisadams (@mrchrisadams) January 16, 2018

There are some angry sounding posts rebuking the arguments in the book, in the replies if you look. I don’t know enough about the background to really comment on them, so I’m staying out of that.

Instead, I’m going to share the ideas that I think were most interesting to me, to help you decide if it’s worth looking into the book and ideas in more detail.

As an aside, the book is very cheap, and a very fast read. You can read it in a few hours – I got home at 10:30, and I had finished the book the following morning before starting work.

Little if any relation between estimates and time taken to deliver work

The key idea I took from his talk was that as an industry, IT is terrible at making estimates, and that the majority of the projects we work on fail.

As the the argument goes, dedicating time to estimating work is counter productive, and should instead should be seen as waste, and something we ought to keep to a minimum.

https://twitter.com/cory_foy/status/427910102742364160

To to support the argument, this chart came up in the book, and also in the talk – what the image shows is that there’s very little relation between the average time taken to deliver a story, and estimated story size.

So, if we’re dedicating all this time to estimating our work, and using it to decide what to do, and if it is this ineffective at giving us useful information to plan with, why are we doing it?

Would it be worth trying not to estimate at all?

Maybe there’s another way?

Not ‘no estimation’, but ‘less estimation’

If you’ve ever used Pivotal tracker, or a burndown chart, what he suggests instead probably won’t be news to you – instead of upfront estimation, it’s wiser to look at work that gets delivered each week, and focus on breaking down stories so they’re:

- small enough to deliver in a set time box (usually a week or two weeks)

- roughly the same size as each other

You can then use this to project forwards to create what he refers to as a forecast instead, and use this to plan instead. If you know how much you’re getting done on average week, then you can projection this rate forwards to work out how much will, or will not be done by a given date.

As I said, this projecting forwards based on past perfomance isn’t massively ground breaking, but he had some interesting ideas about how you might work out what to do instead if you aren’t estimating.

The most interesting idea to me, that I wish was covered more explicitly in the book

One tool to help with a no-estimates approach, that was news to me was the snappily titled Work Complexity Relative Evaluation diagram.

The idea as I understood it, was largely that you can place units of work you think you need to do, along two axes – technical complexity, versus organisational complexity.

You might think of technical complexity as how hard something is to implement, and think through, if you were building it. It might cover how many moving parts there are to think about, and how technically risky it is. The further to the right it is, the riskier, or greater the amount of effort you think you might need.

This axis isn’t concerned with depending on other people, or other teams working with you to get it delivered.

Social complexity, the other axis covers this.

This is more a function of how many people you need to speak to do get something delivered – this might be how many people in other teams you depend on to deliver something, or how easy it is to get another part of an organisation to do something for you, or simply how well understood something is inside your team, outside of the technical axis.

There’s two useful ideas here bundled into these two axes:

- there’s more to delivering a story than how technically difficult it is

- shipping something frequently relies on other parties, and delays often happen outside a time-boxed development cycle

Yes, we have a matrix

Using these axes means you end up with yes – a consultant’s favourite – a two by two matrix.

Instead of spending time estimating every single story along a fibonacci scale, or how many hours and days it might take, in your team, you’d place stories in these four quadrants.

Things in the bottom right, are in shape to work on, and should be small enough to deliver right away, and fairly quickly, assuming they pass the INVEST test.

The time you might spend estimating each story and assigning hours or points to, you would instead spend doing what you can to move things into the bottom left.

Moving things to the bottom left

This typically would be splitting stories into smaller, more independent parts, or coming up with units of work that let you reduce the complexity, or increase your understanding of a problem. The idea is that you break off progressively more of the problem each time, to bring you closer to delivering it, and create some kind of measurable value.

This might be doing some technical research (you might call it a research spike) to share with your team if it’s new, risky technology you’re working with, or running some kind of experiment to see if people click on a button or sign up on a landing page, to see if a feature has interest before dedicating time to building it.

It might also be something a straightforward as getting people from different teams in a room to talk through an API together, or (gasp!) speaking to actual users, and sharing prototypes with them.

Isn’t this just estimating along a different axis?

You can make the argument that there’s an implicit act of estimation going on here, by plotting bits of work on this axis, and that breaking a story down into a thing deliverable in a single day requires you to think about size to do so.

Also, many responses to the book I’ve seen so far take issue with whether the stats for estimates can be used to make the argument core to #NoEstimates – that we’re not very good estimating as an industry, and doing so is harmful.

I think focusing on the misleading, linkbaity hashtag misses a more interesting part of the message, that there’s a world outside the team building features, and that interacting with that world is important, and worth spending time and resources on, even if it feels intensely uncomfortable, and is outside the skills set the team currently has.

I also like the idea that stories as presented here are not necessarily about just delivering code, or nice looking mockups, but showing some progress towards understanding a business problem better, or reducing the risk associated with it.

I think it also implies that coding should probably be the last resort, which I think is good – shipping code is a really expensive, risky way to solve a problem, and once it’s shipped, it keeps being expensive, as it needs to be maintained.

A difficult pill

The product person in me loves this idea, but I think in Berlin, it may be a hard message to hear, and I’ll try explaining why:

One thing I’ve found compared to when working in London, is that (anecdotally) there’s a real focus in Berlin on hiring developers to ship code, and designers to ship sketch/photoshop files over than anyone else who might have the skills you associate with the discovery, like user researchers or some cases, product managers.

You could read last night’s message, as essentially telling companies they’ve hired the wrong skill sets for their product teams, by concentrating on people who build things, based on the assumption that a problem is already well understood, when it might not be.

The other interesting idea in the book – rolling wave forecast

The other idea, that was new to me in the book was the rolling wave forecast.

The diagram below nabbed from the book goes some way to explaining it. It seems to be a weird mix of release plan, roadmap and burn down chart. As far as I can see, it’s supposed to:

- be less detailed over time like a roadmap, to communicate uncertainty of delivering X features by date Y

- give an idea of the sequence of work being done, like a release plan, so you know when your pet feature might make it to users

- highlight when you’re likely to miss a deadline by projecting the current rate of delivering work forward like a burndown chart, to invite discussion about changing priorities, and which parts of a project are most valuable to deliver

NB: – in this diagram, the book presents a collection of user stories as a feature, in the way UX or product people might refer to an item on a roadmap as theme, or perhaps an epic.

I’m not sure this does a better job than any of these, but then again, I’ve never come across one before – if you have no roadmap already, or the idea of a burndown chart sounds like black magic, maybe it’s useful.

I’d be curious about hearing from people who have used one, and where it fits in with the artefacts I listed above.

If you’re curious, you can see all the highlights I made as I read the book on hypothes.is here.

The talk

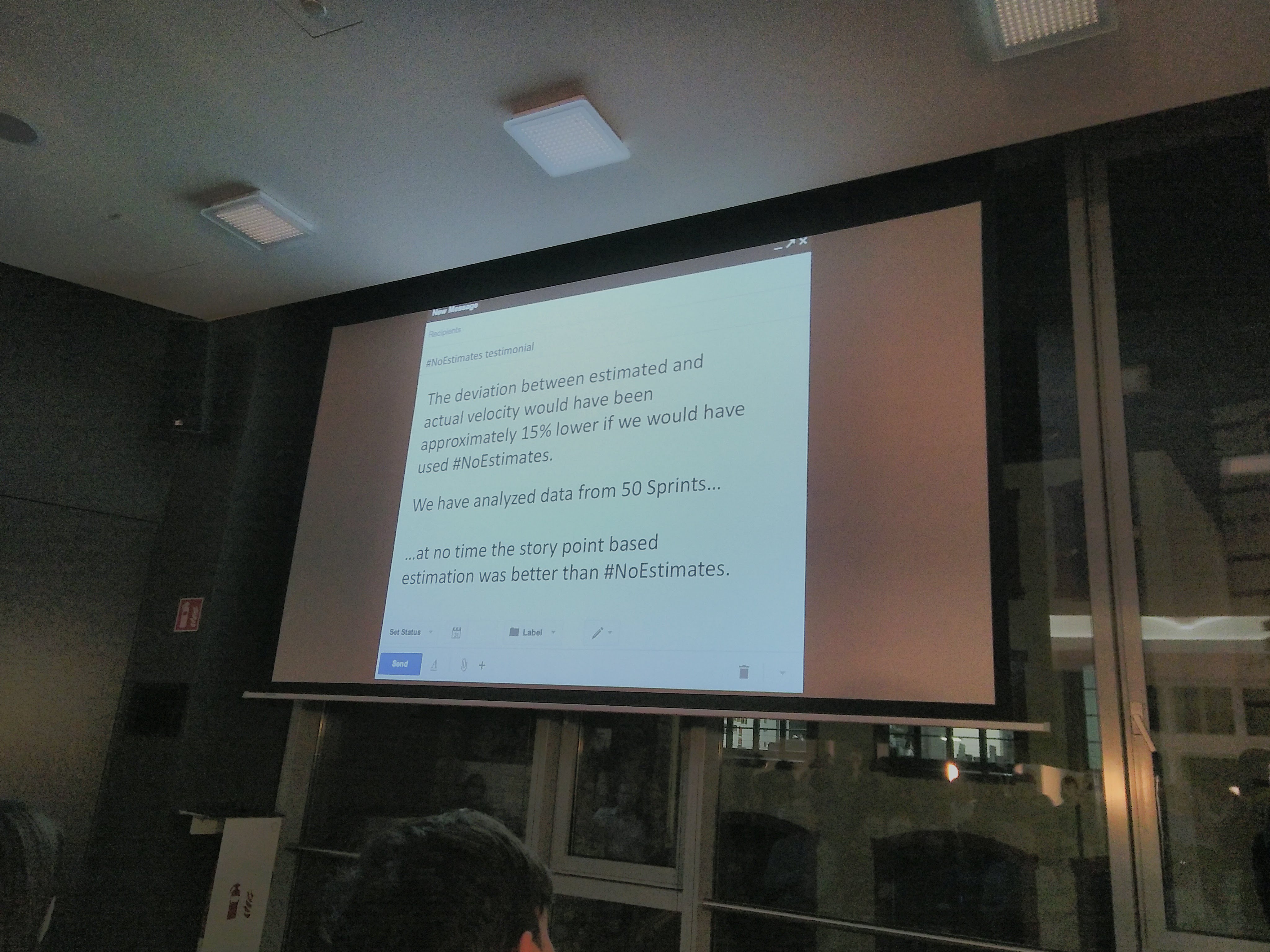

I was a bit turned off by the salesy feel of the talk, and lots of these ideas seem to be ones core to how I understand product management. I took a few pics of slides that I think give an idea of the general feel of the talk, and if nothing else, it was nice to meet long time twitter friend @FJ in person for the first time.

The book

The book is an easy enough read, if like me, you haven’t really paid much attention to the NoEstimates movement, and it was free on the night (which was nice, as I had pretty much decided to buy it, to get a quick summary of the ideas in one place).

Regardless of whether you agree with the ideas ( I don’t agree with all of them myself, and wouldn’t apply them all either, but as I said, there are some interesting ones there), being able to say you’ve read it, and why you agree or disagree is worth more than 7 bucks to me.

So, on along that axis, I’m ahead, I guess. Thanks to Vasco and the BCGDV crew for putting it on – you don’t need to agree with everything someone says to find being exposed to an idea useful, going definitely felt useful.

Feel free to ask questions in the comments, or contact me directly – my DMs are open on twitter and I believe my about page lists all the way you might contact me.

Further links

The Noestimates book has a free first chapter

A rebuttal of arguments in the Noestimates book, part one of a series

Another piece arguing against the presentation style common in the noestimates movement

Estimating without even talking to your team