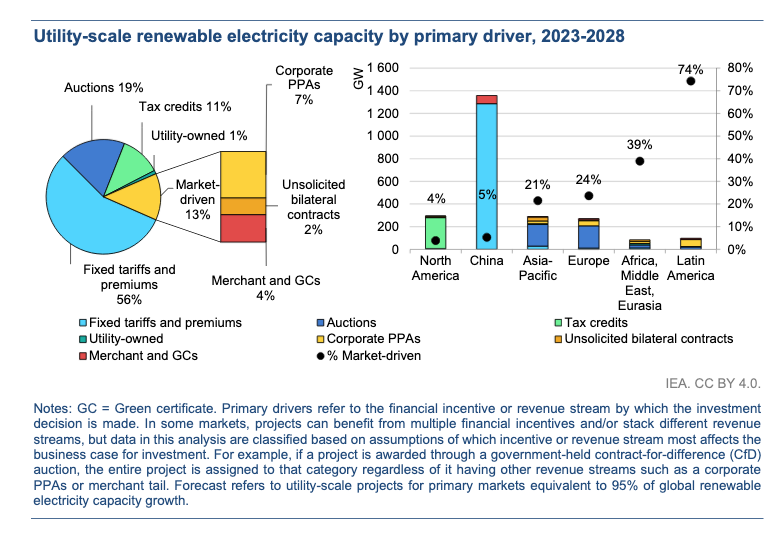

I saw an interesting chart fly by recently from a tweet by Juliaen Jomaux, taken from the recent IEA Renewables report (page 57),

What does this chart tell us?

The key thing that attracted my attention was how in China, the use of fixed-tariffs / premiums, where anyone building a renewables project gets a fixed amount of money per unit of energy delivered or installed for example, is dominant.

I’m in Europe, where we also used to have various fixed tariffs for projects, until in auctions became more popular.

As I understand auctions in Europe have largely been designed along these lines:

- a country says they want to by a given amount of power,

- they then invite participants in the auction to submit a bid, where they say how much they think they can deliver power for

- participants bid

- the winning bids get the contract to deliver the power

So for example, Germany, might say:

“we need 500 MWh of clean energy, every year, for the next 15 years please”.

One various provider might submit a bid, saying they can deliver the power at say… 90 EUR per MWh, and another might say they can deliver it at 70 EUR per MWh. The winner is usually the one who is able to deliver at the lowest price, and also looks like they’re actually capable of delivering.

These are good for bringing down the price of energy on one level, because the competition forces the actors to come in at as low a price point as they can, to win a project. However the flip side is that it can restrict who gets to take part, because submitting a bid is a risky prospect, and not every organisation can survive spending loads of time and effort submitting a bid, losing, it, and then not having any stream of revenue to keep them afloat.

In the Europe until the mid 2010’s, a range of predefined (and to be honest, quite generous) fixed tariffs meant that you had a wide range of actors generating energy, including smaller, community energy organisations and cooperatives, as well as huge corporations.

With the switch to auctions, many smaller providers have dropped out now, leaving only large firms who can afford to lose a few bids to take part. In Europe there are still a few other ways for community energy organisations to take part in the provision of energy, but as the chart above shows, auctions are now much more common.

Yes, this is an oversimplification. You might have multiple winners in an auction, like the top N bids winning, but the key point is that the auction introduces the the idea of actors with losing bids, who come away with nothing.

I understand that auctions might be a way to get better priced energy if you’re a state, but then I see China’s fixed tariff approach, and if you look at the data, you can see that China is deploying much, much more renewable energy than anyone else.

We know that China has a different economic system to Europe, but I was surprised to see how large a part that the fixed tariffs play.

Is there just more appetite to deploy more renewables to meet growing energy demand, than there is to negotiate for the best prices? You can make the case that they are driving the costs down more than any other nation in 2024 through the volume of their purchases, but it’s not clear how the Chinese government captures those savings if they’re paying a fixed tariff price. Maybe they don’t and just accept this as a cost of industry leadership, trusting that Chinese firms will use the profits to invest in new capacity, and spend the money in their local economies wisely? This is essentially what happens with the IRA in the US where the various subsidies almost guarantee healthy profits for many actors.

I have the IEA report in front of me, but if there are other podcasts, or papers, videos, or blog posts that help explain the different way different countries pay for clean energy, with a particular focus on the role fixed tariffs play in the mid 2020’s, I’d welcome the links.

Update: after reading Brett Christopher’s recent book, The Price is Wrong, I now also wonder if one of the factors here is just predictability of income. I really should write a full post, but in the meantime, one relevant thing I learned is that for renewable projects, the cost of the energy you can sell is a really important factor in getting them built because you almost always need finance to pay to build it. Volatile energy pricing is referred to merchant risk – i.e. a risk that you won’t get paid enough for the energy you generate to make the repayments on finance. China’s approach has been to provide a stable, if not-so-generous tariff, as well as offer cheap loans. The first reduces the merchant risk making the cost of borrowing lower. This is supplemented by explicit cheap loans from the state, make borrowing cheaper still. Both make it more likely that a project is ‘bankable’, and more likely to go ahead.