This came up in a recent conversation about sustainability in the digital sector, because the answer isn’t immediately obvious.

To understand it, I think you need to understand why we have antitrust or competition laws in the first place.

When they were first brought about bout in the first half of the 20th century, there was obviously a consumer welfare angle, but the laws also recognised that concentrating so much market power in the hands of a few companies that were primarily answerable to shareholders ahead of society had the effort of distorting the entire democratic process.

It’s not directly about tech or cloud computing, but the snippet linked below is from a fantastic interview with John Farrell at the Institute for US Self Reliance on the Energy Transition Podcast:

So the second part is really that we need to revive more antitrust scrutiny of utilities. So what we’ve got happening in the utility sector is really novel from the standpoint of anti-monopoly policy in the United States. So we have a number of kind of landmark anti-monopoly laws. A lot of them passed right after the Gilded Age in the early 1900s. Some of them were strengthened in the 1950s. And the idea was essentially to prevent the concentration of corporate power in a way that would distort democracy. two purposes. They are supposed to make our economy more competitive and protect smaller producers, but they’re also protecting democracy from outsized political power, which pretty much describes what we would want to have happen in the utility sector.

Emphasis mine in the quote above. In a number of systems like US energy markets, you don’t really get to choose your provider of power – a monopoly is issued to one or more specific organisations. They agree to be regulated by a public utility commission (PUC), in return for guaranteed profits, and being the only provider allowed to act in a given region.

This puts them in a massively powerful position, and in many cases they have already made significant investments in gas and coal fired power stations, that they want their return on. So, rather than accept closing them down, and doing the work to deploy newer, clean power they some of the revenue from their monopoly position for lobbying – to influence lawmakers to kill legislation that might force them to tranistion from fossil fuels, or to place their chosen people on the commission that regulates them.

They are also active on the federal scene, to shape any policy to be as friendly to them being able to make short term returns as possible.

If you were wondering why in the USA, the IRA, the most significant climate legislation passed in memory was basically an all carrot, no stick subsidies bonanza, and what happened to lots of the measures first announced when it was called the Build Back Better Act, this is partly why, and this is detailed in a story in the New York Times in 2021 (link, archive)

Companies with disproportionate influence were able to hollow out lots of the legislation that would have compelled actions that large firms didn’t like the sound of, like introducing minimum corporation taxes, and so on.

Why did they have such disproportionate influence though?

One of the reasons is simply that when companies get large enough, they make enough extra cash to divert to time and money to influencing policy makers. And generally speaking the returns on lobbying tend to be pretty good, especially if you are able to lobby for something that lets you capture most of the concentrated gains for yourself, versus them being more diffuse benefits that help a lot of people, but by a comparitively little amount.

Another is related to the number of companies. If you only have a handful of massive players, it’s relatively easy for them to collude on things that might be good for them, but terrible for everyone else.

As the number of companies grows, it gets harder to get coordinate them, especially if they’re competitors – they form different factions and special interest groups, so the demands become less clear in aggregate.

If you’re a policy maker, rather than hearing one message again and again, you’re hearing multiple conflicting messages – it’s less likely that laws will be passed where you can see the influence of that one message in the text.

What does this have to do with digital sustainability?

While regulated monopolies are one egregious example of this happening, broadly speaking, monopoly power has the effect of taking all kinds of policy off the table, or even framing certain things as inevitable and necessary. I’ll refer to two examples.

AI

One example might be how GenAI is seemingly wedged into every second service online, and the absolutely collosal rollout of digital infrastructure associated with it right now. This might be seen as necessary from the point of view of companies whose existing products like cloud computing and various flavours of SaaS are showing slowing signs of growth, and who need to satify shareholders wanting ever faster revenue growth.

But that’s not the same as being necessary for everyone else.

Cleaner energy

This also shows up in how governments expect the electricity powering the digital infrastructure our world runs on as well. If the primary mechanism that governments in the West rely on is either some form of tax credits, to corporate power purchase agreements, then both of these, for the most part favour very large organisations who have easier access to finance.

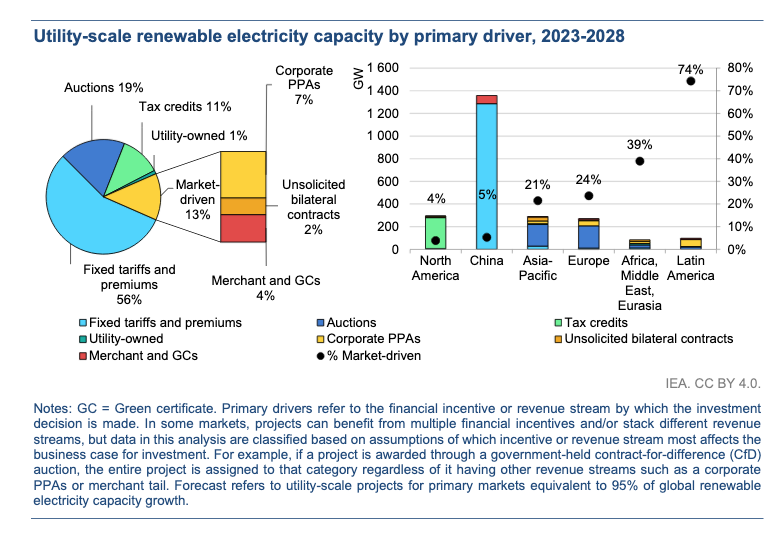

This isn’t the only way to get the clean power built that we need to displace fossil fuels, and the big counter example you can see in the chart below is in China, where instead of governments relying on corporate power purchase agreements as the mechanism to decarbonise the grid, they use different ones like more modest, but predictable tariffs for power instead.

I’ve written more in another post – If you want greener energy, what’s the best way to get it?

Anyway – these are two quick examples. I’m not sure the best ones, but I think they do represent examples of policy that affects the world of digital sustainability, that tend to favour huge companies, at the expense of smaller, more diverse players, who I think would often have somewhat different priorities to those of publicly traded companies in extremely concentrated markets.

Update: I think there’s an interesting angle to explore when talking about alternatives monopoly if our goal is the provision of access to enabling digital services. If we agree the benefits of digital services are transformational, then I think there’s an relying on monopoly providers is a) massively inefficient (see their share buybacks made by big firms to show how expensive it is), and b) not inline with the science on planetary limits (racing each other to deliver massive AI build out, so they end up being the new monopoly). This post here by Alberto Cottica on modes of provision lays out an really interesting framing for talking about how deliver the benefits, that is in-line with the the science around planetary boundaries.