For me at least, one of the most politically exciting things that happened this year was seeing the UK finally get rid of a conservative government and elect one that had to extremely ambitious climate promises in its manifesto. More specifically the goal to reach clean power by 2030 really caught my attention, and coincidentally is somewhat much aligned with one of the demands we have in my day job, of a fossil free Internet by 2030.

I have just finished reading about the plan that was published this week. Here are some key thing that leapt out at me.

So much wind

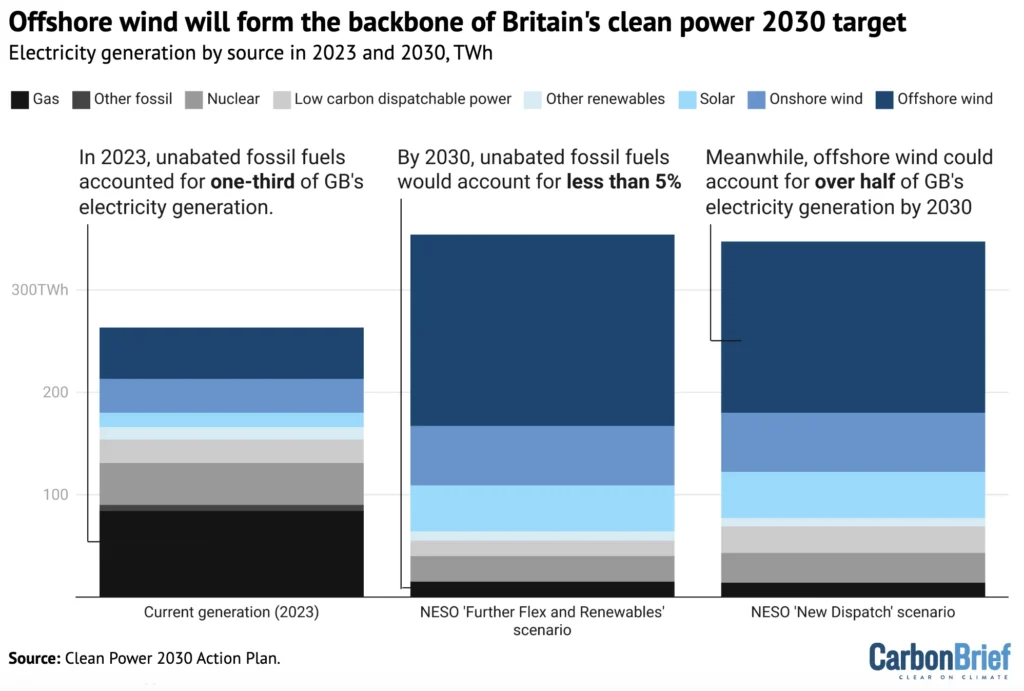

I knew that the UK was a windy place, but wow when you look at the expected power mix in 2030 the amount of wind and in particular offshore wind that the UK will be relying on is just staggering.

More than half of the power that the UK relies on will come from gigantic offshore winter turbines – see the chart below to give you an idea of how things are right now and how they are expected to work in the future.

Offshore wind is one of the success stories for the UK (assuming we look past the scenario under the previous government where one year zero bits were made for one of the offshore wind auctions). And the 2010s, offshore wind was incredibly expensive and made up a tiny proportion of generation and now within 20 years it is making up more than half of all power and one of the major economies of the world.

Not entirely fossil free

One other thing to take into account is that the clean power definition here is not actually 100%. This might sound strange coming from someone calling for a fossil free Internet at work, but to be honest, there are two things to take into account here that make it a slightly easier pill to swallow:

- The final a few percent of decarbonising a grid in most modelling I am familiar with show an incredibly steep increase in cost, as you reach 100% clean power. Given this is only five years away, I can imagine having the 5% wiggle room significantly brought down the cost that policy makers had to sign off on.

- It looks like there would be no new gas generation being built – instead there would still be capacity but the amount is actually used every year (i.e. the capacity factor) would be much much lower. As far as I am aware if you have a system that relies on variable renewables then in the 2020’s to early 2030s at least it looks like having some degree of chemical storage appears to be unavoidable. The fossil-free chemical options that I’m aware of, like green hydrogen or green methanol, even if their price was right are not available at the scale necessary yet.

Swapping fuel for finance

The final thing that I think is worth paying attention to is how people say it will be paid for. There is a commonly used line by people talking about the energy transition, about it very much being a transition from relying on fuel to relying on finance – this is because renewables like wind and solar have an upfront cost but once they are built, there is no fuel to pay for.

I think it’s quite encouraging that this is the line being used to explain how it’s being paid for – the comms appears to be very much about protecting people from the volatility of fossil gas prices, (which have been a source of acute financial pain for so many people in Britain in the last few years), and also saving money by not having to pay for gas in the first place.

This is all probably modelled in Python somewhere, and possibly on a public repo on GitHub

One thing I learned after speaking to lots of energy modellers and listening to lots of podcasts is that the initial 2030 target was at least somewhat informed by reports from the think tank Ember Energy, and those reports relied on energy modelling using some open source software called PyPSA.

There is a public repo on GitHub from the Ember Energy organisation, and I would be surprised if next year there is not some similar project to model this out, even if it is not the “official” one from the UK government.

I really hope we see more modelling like this in the public domain to inform public discourse about how we can get off fossil fuels – I know it is increasingly in use outside of the UK too.

Oh! This reminds me. I opened an issue a while back on that repo, largely because when I read Ember’s reports that had informed the policy decision, I had a bunch of questions about how much flexibility there were relying on. In my day job one thing I hear all the time is how data centres can be a potentially helpful source of this flexibility so I was curious about how that could be modelled. If you know your way around PYPSA and you’d be up for collaborating with me on figuring out how to model this, do please get in touch.

Where to learn more

There is some fantastic analysis from Carbon Brief as ever about the UK’s plan.

I first found out about this I first found out about this from a thread from Emil Dimanchev on BlueSky, detailing the different designs of a recent scheme to purchase of your wind by the government of Denmark and the UK respectively.

You can find the actual report on the UK government website here.